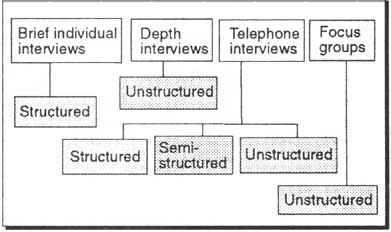

Types of personal interview

The two main types of interviews conducted in marketing research are structured and unstructured.

Unstructured informal interview

The unstructured informal interview is normally conducted as a preliminary step in the research process to generate ideas/hypotheses about the subject being investigated so that these might be tested later in the survey proper. Such interviews are entirely informal and are not controlled by a specific set of detailed questions. Rather the interviewer is guided by a pre-defined list of issues. These interviews amount to an informal conversation about the subject.

Informal interviewing is not concerned with discovering ‘how many’ respondents think in a particular way on an issue (this is what the final survey itself will discover). The aim is to find out how people think and how they react to issues, so that the ultimate survey questionnaire can be framed along the lines of thought that will be most natural to respondents.

The respondent is encouraged to talk freely about the subject, but is kept to the point on issues of interest to the researcher. The respondent is encouraged to reveal everything that he/she feels and thinks about these points. The interviewer must note (or tape-record) all remarks that may be relevant and pursue them until he/she is satisfied that there is no more to be gained by further probing. Properly conducted, informal interviews can give the researcher an accurate feel for the subject to be surveyed. Focus groups, discussed later in this chapter, make use of relatively unstructured interviews.

Structured standardised interview

With structured standardised interviews, the format is entirely different. A structured interview follows a specific questionnaire and this research instrument is usually used as the basis for most quantitative surveys. A standardised structured questionnaire is administered where specific questions are asked in a set order and in a set manner to ensure no variation between interviews.

Respondents’ answers are recorded on a questionnaire form (usually with pre-specified response formats) during the interview process, and the completed questionnaires are most often analysed quantitatively. The structured interview usually denies the interviewer the opportunity to either add or remove questions, change their sequence or alter the wording of questions.

Depth interviews

Depth interviews are one-to-one encounters in which the interviewer makes use of an unstructured or semi-structured set of issues/topics to guide the discussion. The object of the exercises is to explore and uncover deep-seated emotions, motivations and attitudes. They are most often employed when dealing with sensitive matters and respondents are likely to give evasive or even misleading answers when directly questioned. Most of the techniques used in the conduct of depth interviews have been borrowed from the field of psychoanalysis. Depth interview are usually only successful when conducted by a well trained and highly skilled interviewer.

Other instances when depth interviewers can be particularly effective are: where the study involves an investigation of complex behaviour or decision-making processes; when the target respondents are difficult to gather together for group interviewers (e.g. farmers, veterinary surgeons, haulage contractors, government officials); and where the interviewee is prepared to become an informant only if he/she is able to preserve his/her anonymity.

Dillon et al1. believe that to be effective, the interviewer must adhere to six fundamental rules. These are:

he/she must avoid appearing superior or condescending and make use of only familiar words

he/she must put question indirectly and informatively

he/she must remain detached and objective

he/she must avoid questions and questions structure that encourage ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers

he/she must probe until all relevant details, emotions and attitudes are revealed

he/she must provide an atmosphere that encourages the respondent to speak freely, yet keeping the conservation focused on the issue(s) being researched

Depth interviews involve a heavy time commitment, especially on the part of the marketing researcher. Interview transcripts have to be painstakingly recovered, if they are to be accurate, either from terse interview notes or from tape-recordings of the interviews. This can take many hours of often laborious work. The transcripts then have to be read and re-read, possibly several times, before the researcher is able to begin the taxing process of analysing and interpreting the data.

Telephone Interviews

Whilst telephone interviews among consumers, are very common in the developed world, these are conducted with far less frequency in the developing world. The reason is somewhat obvious, i.e. only a relatively small proportion of the total population has a telephone in the house. Moreover, telephone owners tend to be urban dwellers and have above average incomes and are therefore unrepresentative of the population as a whole.

To a greater extent, telephone interviewing has potential in surveys of businesses, government agencies and other organisations or institutions. Even then, it is still the case that telephone surveys are rarely without bias. Whilst it is true that many businesses have a telephone, small businesses and even medium-sized enterprises are far less likely to have access to telephones.

Telephone interviews afford a certain amount of flexibility. It is possible, for example, for interviewers to put complex questions over the telephone. The interviewers can probe, skip questions that prove irrelevant to the case of a particular respondent and change the sequence of questions in response to the flow of the discussion, and earlier replies can be revisited. The interaction between interviewer and interviewee that is possible over the telephone simply is not achievable through a mailed questionnaire. In comparison to personal interviews, telephone interviews do not appear to enjoy any margin of advantage. Perhaps the only advantages are those of speed and cost. Even then, manpower costs in developing countries tend to be very low and so only speed remains as a potential advantage over personal interviews.

In the developed world, the era of computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) has begun. Researchers conduct the telephone interview whilst seated at a computer. Responses are entered directly into the computer, by the interviewer. The screen displays the questionnaire and any skipping of questions, due to earlier responses directing that some questions are not applicable in the case of the interviewee, is controlled automatically by the computer. Since the responses are entered directly into the computer the data is instantaneously processed. The computer can also be programmed to produce standardised marketing reports.

Conducting the interviews

It is essential, for both types of interview format, that the interviewer has a good grasp of the study’s objectives, and of the information that is to be collected. This will enable ‘probing’ to elicit the right data required, and ensure all relevant issues are covered. Furthermore, some respondents may ask why a particular question was included in an interview, and it may be necessary for the interviewer to be able to ‘justify’ particular questions.

In rural areas it is customary before embarking on a formal interviewing survey to notify the relevant public authorities, e.g. village head, district union, etc. to ensure co-operation from respondents. Sometimes individuals may refuse to co-operate unless they are convinced that the interviewer has permission and approval to conduct the survey from the recognised local authorities.

Before commencing on interviews it is as well for the interviewer to prepare what he/she is going to say when he/she first meets a respondent. Decisions need to be made as to whether the respondent is to be told who is sponsoring the study, the purpose of the study, or how the data is to be used, and so on. These points need to be decided beforehand to ensure that a ‘standardised’ approach is used for each interview. Variations in approach style may lead to different types of response from respondents and therefore variations in results. If suitable introductions are prepared in advance, no time will be lost during the interview in lengthy explanations, and a good impression can be created from the start.

Interview approach in the field: It is important that the interviewer keeps as low a profile as possible in the rural setting. Interviewers should walk as much as possible and in small numbers – two in a team is often best. If the research team is large, it is advisable to divide the study area into a number of zones to avoid duplicating efforts or interviewing the same respondents.

Once an individual who appears to be worth interviewing is spotted in the field, it is best not to wander around indecisively creating suspicion. He/she should be approached directly. However, one should avoid startling potential respondents by running up to them and pulling out the questionnaire for interview. Blending into the local context as much as possible is obviously the best strategy. One should always be sensitive to the fact that most people may be suspicious of outsiders.

The timing of the interview can be very important. One should be aware of the daily schedule, seasonal activities, and work habits of potential respondents. For example, if a farmer is irrigating and receives water only once a week for an hour, he/she may not be interested in participating in an interview at that time.

Interview introduction: The introduction to an interview is crucial. A good introduction can effectively gain the respondent’s co-operation and a good interview, but a bad introduction could result in refusal to co-operate or biased responses.

|

Greeting: |

This should be made according to local custom. |

|

Small talk: |

Being approached by a stranger will make the potential respondent feel uncomfortable. It is necessary to help him/her feel at ease by starting with polite small talk about the weather or crop conditions, (in the case of a farmer) or about the health of the family and the general economic climate in the case of non-farmers. |

Overcoming apprehension: The approach of an interviewer is still an unfamiliar experience to most people. Many people are suspicious of outsiders and particularly interviewers. Some may think the interviewer is an ‘official’ who has come to check up on them for taxes. Certainly many potential respondents will fear that the information they give will be used against them at a later date, or that the interviewer is trying to probe family secrets. To ensure cooperation it is important to:

Keep the atmosphere relaxed and informal.

It can be helpful if the interviewer plays down the fact that he/she wishes to conduct a ‘formal’ interview. Respondents can be encouraged to think that the interviewer is interested in conversation rather than interrogation.

Explain why the interview is necessary.

The respondent should be given a brief background as to the nature and purpose of the study. This will bring him/her into the interviewer’s confidence.

Stress the value/benefit of the study to the respondent

Respondents are more likely to co-operate if they think they will ultimately benefit from the study. If one can indicate that as a result of the study it will be possible to develop better and cheaper products for the respondent, then they should be encouraged to co-operate.

Appeal to the instincts of pride and vanity of the respondent

The respondent needs to be made to feel important. He/she needs to be made to feel that the interviewer is particularly interested in his/her opinion because he/she is the ‘expert’ and ‘informed’.

Additional points that may help to put the respondent at ease could include:

Language: It is advisable that marketing researchers should adopt the language of those from whom they hope to obtain information.

“… using local names for socio-economic characteristics, bio-physical characteristics, lands, customs, time, intervals and measures”.

Length of interview: The respondent can be assured that the interview will be brief. It is unwise to be deceitful here, otherwise there is a danger that the interview may be stopped mid-way by an angry respondent.

Confidentiality: The respondent can be assured that the interviewer will not reveal the respondent’s identity (and will use the data only in aggregate form) or give the results to official organisations.

Closing interview: After all relevant topics have been covered or the respondent’s time exhausted, the conversation should be brought to an end. If the weather is unfavourable (too hot or too wet) or the respondent seems pressed for time it is best to prematurely stop the interview. The departure is best done gracefully, naturally and not too abruptly. The business-like ‘Got to go’ departure should be avoided. The respondent should be thanked for his/her time and given the appropriate customary farewell.

Interview recording

All the best interviewing is useless if it has not been adequately recorded, so it is important to ensure good recording conditions. In an open-ended interview it is difficult to make notes on everything during the interview. The best approach in team-work is to appoint a scribe, i.e. a person whose job it is to write everything down. How long one waits before writing up full field-notes depends on the setting, and the interviewer’s personal style but it should be borne in mind that an interviewer’s memory is limited. It is surprising how facts, ideas and important observations that one thinks one will never forget quickly slip away. Half of the details from an interview can be forgotten within 24 hours, three-quarters can be lost within 2 days and after this only skeletal notes can be salvaged. Jotted notes will help prompt memory later, but it is best to write up interview notes while they are still fresh in the interviewer’s mind after the interview or at the end of the interviewing day.

Use of tape-recorders: A tape recorder can often be useful. It enables the interviewer to give THE respondent his/her full attention during the interview and avoid the need to be constantly scribbling notes. It can also enable data to be left until such time as analysis can be applied more rigorously and in a more leisurely way. It should be borne in mind, however, that not everyone likes to be tape-recorded. If taping is contemplated the respondents’ permission should be sought first.

Sources of error and bias

In personal interviews there are many ways in which ‘errors’ can be made by both the respondent and the interviewer, and this can lead to ‘bias’ in the results. The objective of the interviewer should be to minimise the likelihood of such bias arising.

Respondent induced bias

Faulty memory: Some respondents may answer a question incorrectly simply because they have a poor memory. The key to avoiding this problem is to steer clear of questions requiring feats of memory. For example, questions such as, “Can you tell me what your crop yield was four years ago?” should be avoided. Other aspects of faulty memory that were mentioned in the previous chapter were telescoping and creation.

Exaggeration and dishonesty: There can be a tendency on the part of some respondents to exaggerate claims about their conditions and problems if they think it will further their cause and lead to improvement in their well-being. The interviewer must be alert to, and note any, inconsistencies arising. This is best achieved by checking key pieces of information with a variety of sources.

Failure to answer questions correctly: If rapport is not developed sufficiently, the respondent may be unwilling to respond or fail to give sufficient attention or consideration to the questions asked, and if the respondent does not understand a question properly he may give inappropriate answers. The interviewer needs to ensure that the respondent fully understands the questions being asked and is responding in the appropriate context.

Misunderstanding purpose of interview: Some respondents may perceive the purpose of the survey to be a long-winded form of ‘selling’, particularly if the interviewer is asking them what they think about a new product. Their comments, therefore, about such issues as ‘propensity to purchase’ need to be looked at within a context where they may be expecting to have to buy the product at some stage and are trying to strike a hard bargain. To avoid such problems arising it is important to carefully explain the objectives of the survey, the identity of the interviewer and sponsor, and what is required of the respondent, prior to the interview proper.

Influence of groups at interview: During interviews the presence of other individuals is almost inevitable. Most of the time other family members or neighbours will wish to join in the discussion. Such a situation has can have important implications for the type of data obtained. The respondent may be tempted to answer in a way that gives him/her credibility in the eyes of onlookers, rather than giving a truthful reply. In circumstances where the presence of third parties cannot be avoided, the interviewer must ensure as far as possible that the answers being given are the honest opinions of the individual being interviewed. The interviewer must again be alert to inconsistencies and closely observe and monitor the way in which the respondent is reacting and interacting with those around him.

Courtesy bias: In interview situations it is quite possible that one will come across the problem of courtesy bias, i.e. the tendency for respondents to give answers that they think the interviewer wants to hear, rather than what they really feel. The respondents may not wish to be impolite or to offend the interviewer, and may therefore endeavour to give ‘polite’ answers. Courtesy bias can be an obstacle to obtaining useful and reliable data and therefore needs to be minimised. Generally, however, the creation of a good interview environment and an appropriate relationship between the interviewer and the respondent can help avoid too much courtesy bias arising:

Bias induced by interviewer

It is also possible for the interviewer him or herself to introduce bias into an interview, and this must be avoided at all costs.

Desire to help the respondent: The interviewer may become too sympathetic to the problems and conditions of the respondent, and this can affect the conduct of, and results obtained from, the interview. Objectivity must be retained at all times.

Failure to follow instructions in administering the questions: It is often tempting for the interviewer to change the wording of a question or introduce inflections in questions. This can affect the respondent’s understanding and can bias his/her replies. Particular problems may arise if the respondent does not understand the question as stated and the interviewer tries to simplify the question. The altered wording may constitute a different question. When questions are open-ended, this can involve the interviewer in formulating probing questions that go beyond the printed words. Unless the probes follow instructions faithfully the potential for bias is great.

Reactions to responses: When respondents give answers, the interviewer must be careful not to ‘react.’ A note of ‘surprise’ or ‘disbelief may easily bias the respondent’s subsequent answers. Interviewers must respond with a uniform polite interest only.

Focus group interviews

Focus group interviews are a survey research instrument which can be used in addition to, or instead of, a personal interview approach. It has particular advantages for use in qualitative research applications. The central feature of this method of obtaining information from groups of people is that the interviewer strives to keep the discussion led by a moderator focused upon the issue of concern. The moderator behaves almost like a psycho-therapist who directs the group towards the focus of the researcher. In doing so, the moderator speaks very little, and encourages the group to generate the information required by stimulating discussion through terse provocative statements.

Characteristics of focus group interviews

The groups of individuals (e.g. housewives, farmers, manufacturers, etc.) are invited to attend an informal discussion. Usually between 6 and 8 participants are involved and the discussion would last between 1 and 2 hours. Small groups tend to lose the mutual stimulation among participants, whilst large groups can be difficult to manage and may prevent some participants having the opportunity to get fully involved in the discussion.

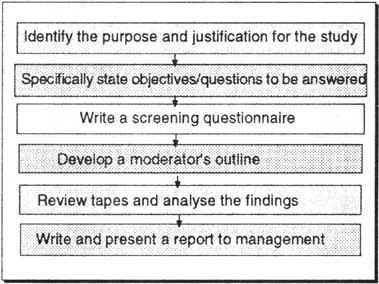

The researcher raises issues for discussion, following a ‘guide list of topics’ rather than a structured questionnaire. The participants are encouraged to discuss the issues amongst themselves and with the researcher in an informal and relaxed environment. The researcher records comments made by the participants (usually utilising a tape or video recorder). Figure 5.2 shows how this list of topics is arrived at.

In contrast to a personal interview survey, the number of interviews in a typical group interview survey is very small, usually between 3 and 4 would be sufficient for each type of respondent-sector (e.g. farmers or manufacturers). Generally from the first interview on an unfamiliar subject the researcher will learn a great deal. The second and third interviews will produce more information, but not all of it will not be new. By the fourth interview most of what is revealed will have been covered before, and the diminishing returns involved would generally not justify the cost of further groups.

The participants within a focus group are selected in such a way that they exhibit a high degree of homogeneity with respect to either background, behaviour or both. Consider, for example, a study carried out by a small African nation that is looking for a niche market for a new range of sparkling wines. It is decided that, as a first step, a series of focus groups be conducted. The researchers are keen to ensure that each group comprises people who are similar in age and behaviour with respect to wine consumption. Figure 5.3 depicts the kind of screening questionnaire that the marketing researcher would use.

Figure 5.3 An example of a screening questionnaire

|

WINE CONSUMPTION FOCUS GROUP SCREENER | |||

|

Hello, I am from Marketing Research Centre and we are conducting research among people who enjoy drinking wine and 1 would like to ask you a few questions. | |||

|

1. Do you or does anyone in your household work in any of the following professions: marketing research, advertising, public relations, or in the production or distribution of wine? | |||

|

Yes |

terminate and tally | ||

|

No |

continue | ||

|

2. Have you participated in a group discussion, survey, or been asked to test any products for market research purposes in the past 6 months? | |||

|

Yes |

terminate and tally | ||

|

No |

continue | ||

|

3. Have you purchased and/or consumed any wine during the past 3 months? | |||

|

Yes |

terminate and tally | ||

|

No |

continue | ||

|

4. Are you currently under medical treatment which prevents you from drinking wine at the present time? | |||

|

Yes |

terminate and tally | ||

|

No |

continue | ||

|

5. Next I am going to read you a list of statements about drinking wine. Please tell me if any of the following statements apply to yourself. (Circle the letters that appear alongside the statements that apply to you). | |||

|

a. I prefer sparkling wines to any other type. | |||

|

b. I often drink sparkling wines although it is not my preferred type of wine. | |||

|

c. I only occasionally drink sparkling wine. | |||

|

d. I have tried sparkling wine and did not like it so I never drink it. | |||

|

e. I have never tried sparkling wine. | |||

|

6. Which of the following groups include your age? | |||

|

under 18 |

terminate | ||

|

18-24 | |||

|

25-29 | |||

|

30-39 | |||

|

40-49 | |||

|

50-59 | |||

|

60 and older |

terminate | ||

|

7. Sex (by observation) | |||

|

Male |

check quotas | ||

|

Female |

check quotas | ||

The first two questions will eliminate those who are likely to be too aware of the focus group process and distracted from the research topic. Questions 3 and 4 prevent those whose experience of wine consumption is not sufficiently recent from taking part. Question 5 would enable the researcher to allocate prospective participants to homogeneous groups. Thus, for example, there may be a group comprised entirely of people whose favourite wine is one of the sparkling wines. Other groups would be made up of people who have never tried sparkling wine and another may involve those who have tried and rejected sparkling wine. Clearly, the line of questioning would be different in emphasis for each of these groups. Question 6 also helps the researcher balance groups in terms of age distribution or he/she can make sure that only people within a narrow age range participate in a particular group. The seventh question allows the researchers to keep to whatever male/female ratios are appropriate given the research topic.

One has a choice of three different types of venue for group interviews, each having particular advantages and problems. Firstly, one could hold interviews at or near farmers’ or manufacturers’ residences. Such a venue has the advantage that the participants would feel they are on safe ground and may therefore feel more secure to express candid opinions, and also the advantage that the participants do not incur expense in attending the interview. However, such a venue can be problematic to organise, costly for transportation if equipment is to be demonstrated, and it can be difficult for the researcher to retain control over the interviewing environment.

Secondly, one could select a ‘neutral’ location such as a government agricultural research centre or a hotel. Again, here, one might avoid respondents’ fears of attending, but there are still the problems associated with organisation, transportation of equipment, and the deterring cost involved for those participants who have to travel to the venue.

Group discussions can be invaluable research instruments for investigating why individuals behave in a particular way. They can be used to uncover motives, attitudes, and opinions through observing and recording the way the individuals interact in a group environment. Group discussions are used primarily to generate in-depth qualitative information rather than quantitative data, and are generally applied in the context of evaluating individuals’ reactions to existing products or new product/concept ideas.

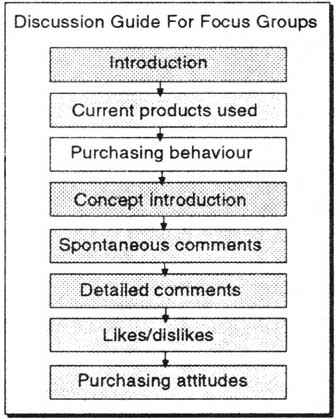

Figure 5.4 gives an outline of how a focus group session is typically structured. This example assumes that the problem to hand involves a concept (or idea) for a new product.

Group discussions are also useful as a cost-effective means of generating background information and hypotheses on a particular subject prior to the launch of a quantitative survey. In this respect group interviews can have advantages over personal interviews in a number of ways:

Synergism: The combined effort of the group will produce a wider range of information, insight, and ideas than will the accumulation of responses of a number of individuals when these replies are secured in personal interviews.

Snowballing: A bandwagon effect often operates in that a comment by one person triggers a chain of responses from other participants.

Stimulation: Usually after a brief introductory period the participants become enthusiastic to express their ideas and feelings as the group begins to interact. In a personal interview, the respondent may not be willing to expose his/her views for fear of having to defend his/her view or fear of appearing ‘unconcerned’ or ‘radical’. Like most animals, the human being feels safer psychologically – as well physically – when he/she is in a group.

Spontaneity: Since no individual is required to answer any given question in a group interview, the individual’s responses can be more spontaneous, less conventional, and should provide a more accurate picture of his position on some issues. In short, respondents are able to speak when they have definite feelings about a subject and not because a question requires an answer.

Serendipity: It is more often the case in a group interview than a personal interview that unexpected responses or ideas are put forward by participants. The group dynamics encourages ideas to develop more fully.

Specialisation: The group interview allows the use of a more highly trained, but more expensive, interviewer since a number of individuals are being ‘interviewed’ simultaneously.

Scientific scrutiny: It allows closer scrutiny in several ways: the session can be observed by several observers. This allows some check on the consistency of the interpretations. The session can be taped or even video-taped. Later detailed examination of the recorded session allows the opportunity of additional insight and also can help clear up points of disagreement among analysts with regard to exactly what happened.

Figure 5.5 lists some of the main applications of focus groups in marketing research.

Figure 5.5 Applications of focus groups

|

APPLICATIONS OF FOCUS GROUPS | |

|

New product development | |

|

Positioning studies | |

|

Usage studies | |

|

Assessment of packaging | |

|

Attitude and language studies | |

|

Advertising/copy evaluations | |

|

Promotion evaluations | |

|

Idea generation | |

|

Concept tests…. | |

Problems with group interviews

While group interviews have many advantages as a research instrument for market research it should be borne in mind that they also have inherent problems. Careful planning and management is required to obtain the most value from group-based surveys.

Qualitative data: The researcher cannot produce hard quantitative data or conduct elaborate statistical analysis because of the usually small number of participants involved in group surveys. It is unlikely that one will be able to include a statistically representative sample of respondents from the population being studied.

Analysis: Analysis of the dialogue produced by group interviews can be a difficult and time- consuming process. This point was made earlier where the time taken to create transcripts from brief notes or tape recordings can take many tedious hours. Thereafter the researcher has to analyse and interpret these transcripts.

Potential biases

There are many potential opportunities for bias to creep into the results of group discussions:

Some participants may feel they cannot give their true opinions due to the psychological pressure on them arising from their concern as to what other members of the group may think. Some may feel tempted to give opinions that they feel will be respected by the group.

The presence of one or two ‘dominant’ participants may repress the opinions of others. Some may not feel confident about expressing an opinion. Some may prefer to submit to the opinions of others rather than cause conflict/argument to develop.

Comparisons across groups: When a number of group interviews are being conducted, comparisons of the results between groups can be hampered if the setting, mix of participants, and/or interviewer is varied. Different interviewers may vary the way they ask questions and vary the order of questions in response to the answers being given. Differences in the settings of different groups may produce variability in the quality of results.

These potential problems should not be taken as reasons for avoiding using group discussions. The advantages far outweigh the problems, and careful planning and management will avoid many difficulties arising in the first place.

Role of the researcher/moderator in discussion group

The researcher organising the group discussion acts as a ‘moderator’ not an interviewer. The purpose of the interview technique is to get others talking and interacting amongst themselves, and does not involve an interviewer asking them a pre-set series of questions. The role of the researcher is thus to moderate the discussion, encouraging participants to talk, prompting the discussion in appropriate directions to ensure all issues are covered, and changing the direction of the discussion when a point is felt to have been sufficiently covered. The moderator is also required to ‘control’ the group interaction to ensure that the viewpoints of all participants are allowed to be expressed.

In every interview situation one will find three types of participant who will need to be controlled:

|

The Monopolist: |

the participant who wants to do all the talking. The moderator must allow him/her a say, but ensure that he/she is quietened when others wish to express an opinion. |

|

The Silent Shy: |

The participant who cannot bring himself to participate. Direct questioning of such individuals is often necessary to produce full co-operation and contribution. |

|

The Silent Aggressive: |

The participant that has plenty to say, but believes he is no good at articulating it. The moderator needs to probe his feelings and have these discussed by the others in the group. |

The moderator has to identify and minimise the effect of these types of participant. By anticipating the likely behaviour of individuals, the moderator can be in a better position to maintain continuity and an easy exchange of opinions and thoughts between individuals.

Questions and prompts must be completely free of bias. The discussion must consist of genuine opinions of the group participants and not ‘assisted answers’. The neutrality of the moderator must be maintained at all times. It is also important to ensure that the interview atmosphere is not too artificial. In group interviews which aim to uncover attitudes towards products, it is always helpful to have the product concerned available (and, if possible, demonstrated or tried by respondents) to elicit realistic and valid opinions.

It is important in the group interview situation that the moderator is not so involved in writing/recording participants’ comments that he cannot listen or react to the discussion which ensues. For this reason it is recommended that group interviews are tape-recorded (audio or visual, where possible). Subsequent analysis can then be more comprehensive, more rigorous and can be conducted at a more leisurely pace.

Due to the nature of group discussions and the number of participants involved, the data obtained can only be qualitative. Analysis is problematic (particularly in deciphering which participant said what) but appropriate qualitative techniques are available and should always be used. Tape recordings of discussions should be fully transcribed, reduced and processed, and their content analysed.

Constructing the interview schedule

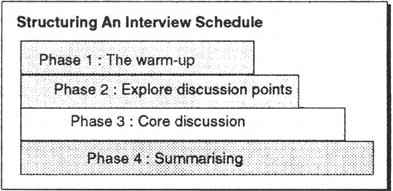

The interview schedule has at least four distinct sections: the warm-up, exploration of discussion points, the core discussion section and a summary.

The warm-up: This section has the objective of creating an atmosphere conducive to an open an free-flowing discussion. One technique that can be used to break down the initial bashfulness among group members who, in most instances, are strangers to one another is to divide them into pairs and exchange simple facts about themselves (e.g. their names, details of the families, place of work, interests etc.). Each group member is then asked to introduce their neighbour to the rest of the group.

The warm-up phase of the session then moves on to encourage the group members to engage in a free-ranging discussion around the topic upon which the discussion will eventually focus. For example, a municipal authority considering establishing a new fruit and vegetable wholesale market positioned outside a congested city centre would ultimately wish to determine what innovative facilities might attract traders to use the new market which is less convenient to them in terms of location. During the warm-up phase the moderator will direct the discussion in such a way as to obtain general information on how participants currently behave with respect to the topic, issue or phenomenon under investigation. The emphasis is upon a description of current behaviour and attitudes. For instance, the traders would be asked to describe their own modes of operation within the wholesale market as well as those of fellow traders.

Exploration of discussion points: In this phase the discussion moves on to the participants’ attitudes, opinions and experiences of existing products, services (or in this case facilities) and on to what they like and dislike about those products/services. With reference to the wholesale markets example, at this stage traders would be invited to comment on the advantages and disadvantages of the facilities within which they currently operate.

Core discussion: This part of the group discussion focuses directly upon the principal purpose of the research. The flow of the session moves on to the participants’ perceptions of new concepts, possible developments or innovations. The wholesale traders, for instance, would be guided towards discussing peri-urban wholesale markets and the kinds of facilities which might attract traders like themselves. A common approach is to follow a sequence of first exploring the ideas which participants generate themselves and then to solicit participants’ reactions to ideas preconceived by researchers, or their clients, about possible future developments.

Summary: The final phase of the focus groups session allows participants to reflect upon the foregoing discussion and to add any views or information on the topic that they may have previously forgotten or otherwise have omitted. A common tactic is to conclude the session by inviting the group, as well as its individual members, to “advise the manufacturer” (or whoever) on the issue at hand.